Following The Money: Inside the Hidden Economy of Online Child Exploitation on Telegram

Operation Marya, internally known as Operation Mariatu during its early stages was launched in December 2024 as DWK’s systematic countermeasure to the escalating trade of child sexual abuse and exploitation materials (CSAEM/OSAEC) circulating in encrypted platforms.

Its first report, released in February 2025, exposed the existence of large Telegram communities with thousands of members sharing and selling illicit content involving Filipino minors. The investigation drew the attention of the Philippine Senate, which later that month initiated a hearing on how “emerging technologies” are being weaponized to commit sexual crimes against children based substantially on DWK’s demonstrations.

Nearly a year later, Operation Marya has evolved into a large-scale digital surveillance initiative. Within Telegram alone, Deep Web Konek has monitored more than 217 channels and groups, not including Facebook pages, Messenger clusters, private group chats and other platforms where minors unknowingly interact with predatory adults. Many participants appear to be minors themselves, either as victims or as members conditioned to normalize exploitative content.

This report presents the first fully verified batch of sellers, anonymized for investigative integrity. They represent only a fraction of the 50+ sellers under active profiling, but their operations expose a structured, financially motivated ecosystem that continues to thrive despite platform takedowns, public pressure, and heightened scrutiny.

• SELLER PROFILES & DETAILED ANALYSIS

1. LunaBlue: The Dark-Web Distributor

Estimated Income: ₱89,869.08

LunaBlue operated with the sophistication of a seasoned digital criminal within his/her distribution network, active from October 11 to 26, fused Telegram-based deployments with dark-web mirroring, ensuring content redundancy even after takedowns. Their offerings included curated bundles of minors’ videos, multi-channel archive access, and even dark-web–hosted packages accessible through Tor links.

The seller relied heavily on circular marketing, resharing teasers across multiple feeder channels, and using disappearing messages to evade detection. Transactions were verified through constant payment proofs, showing a rapid sales cycle and a consistent influx of new buyers. Their system demonstrated a level of operational maturity seen only in large wholesalers who maintain stable content pipelines sourced from multiple upstream suppliers.

2. Atabrix — The Massive Bulk Supplier

Estimated Income: ₱92,875.97

Atabrix functioned as a wholesale-level content farm, running a multi-tier distribution model offering everything from 500-file starter bundles to sprawling 100,000-file mega archives. Their catalog included Filipino minors (“Pinoy keedz/b@ta”), foreign minors, niche fetish-driven folders, AI-manipulated celebrity content, and multi-channel link collections.

Operating from August 27 to October 24, Atabrix recorded 591 verified transactions, one of the highest conversion counts observed. His/her file structure reveals sustained access to upstream exploitative communities suggesting they act not only as a seller, but also as a bulk supplier to smaller resellers who repackage their content.

3. M-Sapphire — The Structured Multi-Channel Operator

Estimated Income: ₱115,651.24

M-Sapphire’s system is one of the most sophisticated Operation Marya has seen. This operator manages a network of Telegram groups for every stage of their distribution chain: payment validation, preview galleries, teaser channels, link repositories, and endorsement spaces for partner sellers.

Their structure resembles a subscription service, featuring “lifetime access,” weekly updates, and auto-disseminated folders. Though full transaction logs were incomplete, the available data already exceeds ₱115,000 in confirmed revenue placing M-Sapphire among the top-tier sellers who maintain long-term, well-planned operations intended to survive bans through seamless backup channels and bot automation.

4. ArchiveVendor — The Industrial-Scale Mega Archive Controller

Estimated Income: ₱120,000 ( midpoint estimate)

ArchiveVendor manages what may be described as an industrial library of child exploitation content. With at least 36 channels and over 105,000 files monitored, ArchiveVendor maintained near-weekly updates, suggesting consistent sourcing from multiple networks. Packages ranged from ₱99 entry bundles to ₱1,099 full-access subscriptions. Because Telegram sometimes conceals historical channel joins, exact sales figures were not fully retrievable. However, using DWK’s dataset from comparable sellers:

Sellers with 50k–100k files earn: ₱70k–₱150k/month

Sellers with weekly updates & 100k+ files may exceed ₱150k/month

To avoid overestimation, DWK uses a conservative midpoint of ₱120,000 for this report.

5. StormPromo — The Seasonal Flash Seller

Estimated Income: ₱11,100

StormPromo embodies the “casual but high-speed” seller model. Their widely circulated “BAGYO PROMO” marketed a 10,000+ file package and a 26-channel bundle at ₱300, relying on urgency-driven messaging (“37 slots only,” “paunahan lang”). This psychological tactic, common among minor sellers generates quick bursts of income before accounts vanish or get banned. Despite the lower scale, StormPromo’s case shows how small operators contribute to the ecosystem by distributing pre-compiled bulk packages originally sourced from larger wholesalers.

6. YarnDistributor — The Small Feeder Reseller

Estimated Income: ₱2,190

YarnDistributor reflects the typical entry-level seller: low-cost bundles (₱150–₱1,000), minimal marketing, and few confirmed transactions (14 during monitoring). Despite its limited reach, YarnDistributor plays a vital role in the network by serving as a feeder account, redistributing materials from larger suppliers to smaller buyer clusters.

Their activity, while modest, demonstrates how even micro-scale operations contribute to the circulation and normalization of illicit content.

TOTAL ESTIMATED REVENUE OF THIS FIRST BATCH: ₱431,686.29 (combined estimate)

This total represents revenue from only six sellers — roughly 12% of the 50+ sellers currently under DWK verification. In the coming months, more sellers will be added to the list as the team continues to monitor them through our Cybercrime Monitoring Center. The real size of the OSAEC economy across encrypted platforms is much larger.

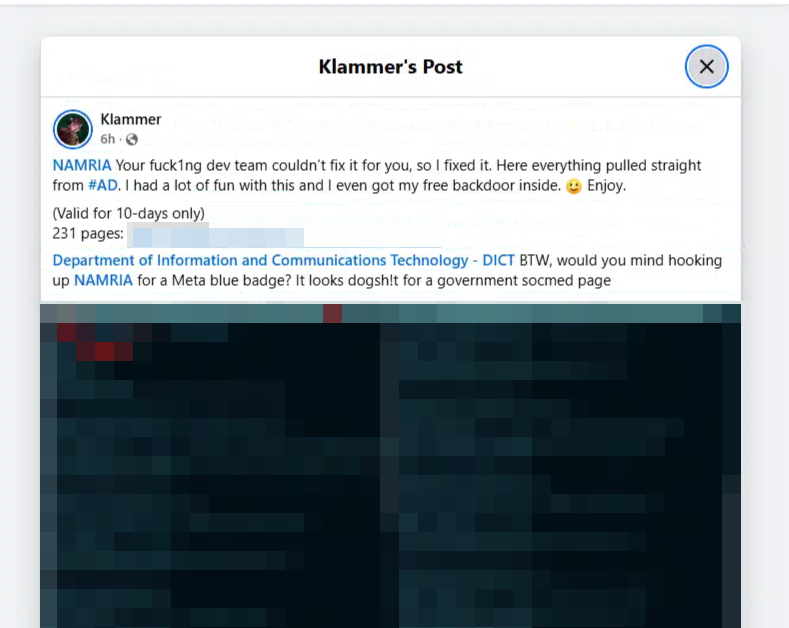

The first batch of verified sellers profiled by Operation Marya relied almost exclusively on digital wallets, particularly GCash, to process payments. Traditional banking methods were absent, and cryptocurrency usage was limited. This reliance highlights the structural role e-wallets play in enabling rapid, low-friction transactions in online markets, including those trafficking in exploitative content.

The issue is not a matter of fault but of system design and implementation. Digital wallets are engineered for convenience, speed, and accessibility, and those same features are being leveraged to facilitate illicit activity.

This raises several key questions: how are micro-transactions from newly created accounts monitored, and why do patterns suggestive of abuse sometimes go undetected? How robust are verification processes in preventing access by underage users or individuals circumventing identification protocols? Furthermore, to what extent do behavioral analytics and pattern recognition tools scan transaction metadata for indicators of OSAEC-related activity?

Available evidence suggests that while e-wallet platforms possess advanced AI, anomaly detection, and automated compliance mechanisms, sellers continue to exploit operational blind spots. Rotation of accounts, fragmentation of payments, and coded transaction references are used to evade detection, creating an environment in which major wholesalers achieve high revenues, mid-tier sellers operate with little disruption for months, and minors can both access and redistribute content.

This emphasizes systemic limitations rather than malfeasance. Platforms have the technological capacity to flag unusual transaction patterns, but there appears to be a lag in integrating these systems specifically for child exploitation contexts.

Our team highlights that closing these gaps will require not only technological enhancements but also structured collaboration between financial service providers, investigators, and regulatory bodies, creating a feedback loop that strengthens detection without compromising legitimate user access.

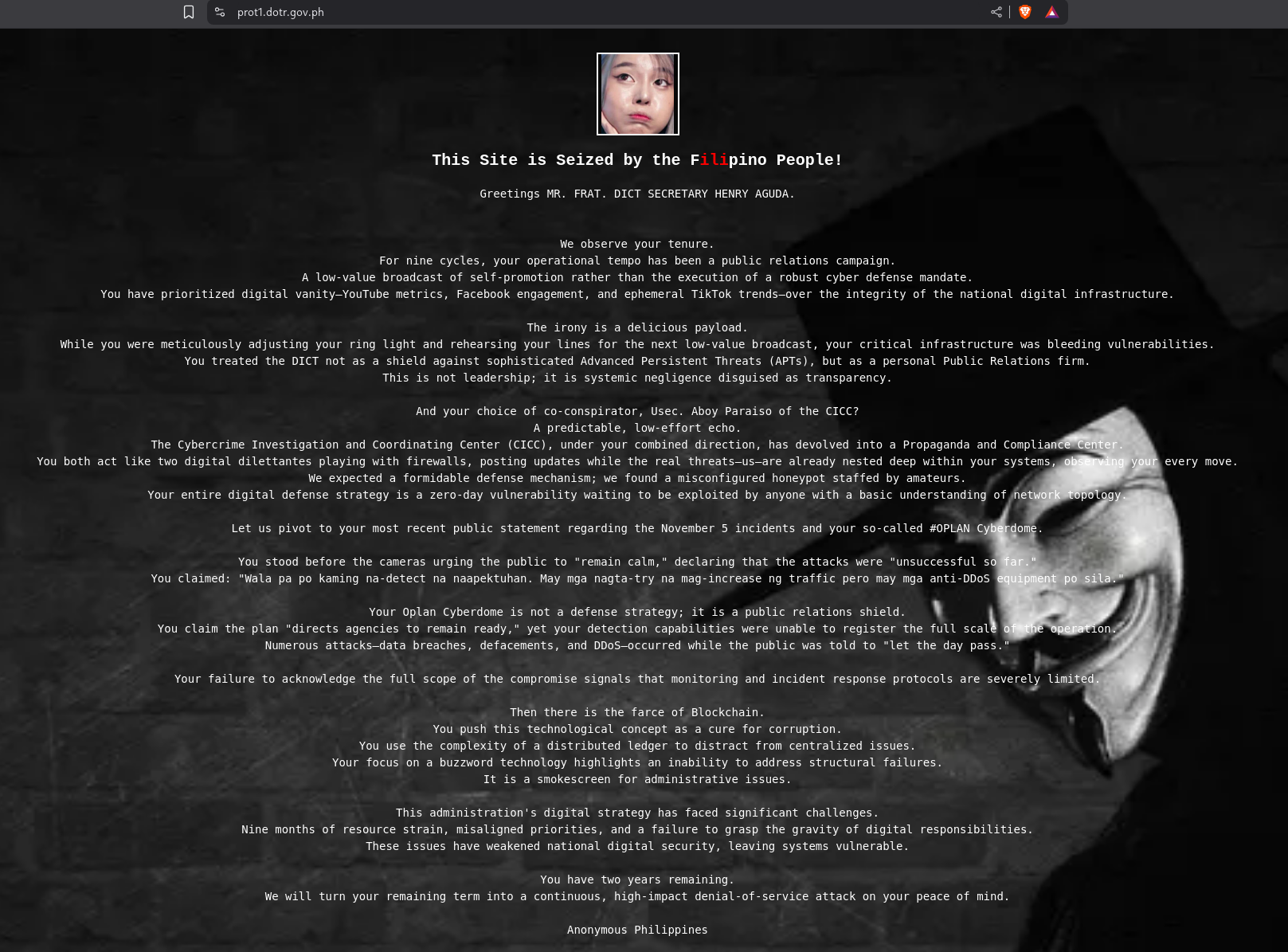

Following the Philippine Senate hearing in February 2025 on emerging technologies in child exploitation, law enforcement agencies increased cyber patrols, inter-agency coordination, and takedown operations targeting channels identified as part of the OSAEC ecosystem. However, DWK’s ongoing monitoring reveals that the speed and adaptability of these networks often surpass the response capabilities of government institutions.

Encrypted platforms allow for near-instant recreation of banned channels, while cross-border hosting arrangements complicate jurisdictional enforcement. Minors are increasingly both unintended victims and participants in content circulation, adding layers of complexity to regulatory and protective efforts. Perpetrators rapidly incorporate technological innovations, automation, subscription-style access, and anonymized links making enforcement reactive rather than proactive in most cases.

This evolving environment reflects structural challenges rather than negligence. Agencies are constrained by legislative frameworks, resource allocation, and the inherent speed of digital ecosystems. DWK emphasizes that effective intervention requires a shift from reactive takedowns to data-driven, predictive enforcement, combined with international collaboration and the integration of platform-level monitoring. Regulatory progress is being made, but the landscape underscores the need for agile, technologically informed strategies capable of keeping pace with the operational sophistication of these networks.

Taken together, the patterns observed in digital wallet usage and government response illustrate an adaptive underground economy. The market persists not because of any single failure, but because systems like financial, technological, and regulatory are not fully aligned to detect and disrupt exploitative patterns at scale. It also suggests that structural interventions are essential: enhancing platform-level AI detection, refining verification protocols, fostering collaboration across agencies and service providers, and maintaining constant monitoring of emerging digital behaviors.

Such an approach balances the need for child protection with operational neutrality, framing the issue as a challenge of systems and structures rather than individual culpability. Only by addressing systemic vulnerabilities across both private and public sectors can the underlying mechanisms sustaining this economy be meaningfully disrupted.

https://iili.io/fqv8Q6B.jpg

https://iili.io/fqv8PZx.jpg

https://iili.io/fqv8sCQ.jpg

https://iili.io/fqv8Da1.jpg

https://iili.io/fqv8b8F.jpg

https://iili.io/fqv8myg.jpg